Summarizing 50+ articles on Startup Ideas: Exploration, Identification, & Evaluation

I summarized the best posts and podcasts on startup ideas by the world's most successful founders and VCs, including Andy Rachleff, Thiel, Naval, Andreessen, Khosla, Rabois, Geoff Lewis, PG, & more.

Millions of hours have been wasted working on bad startup ideas. Saying that ideas are worth nothing or that the low-hanging fruits are picked is false. Knowledge is the most valuable resource in the universe1, and the universe is infinite.

But what makes a good startup idea, secret, or technology inflection point? And how do you find them? In this article, I summarize 50+ blog posts and podcasts on the topic of startup ideas by the world's most successful founders and VCs (including Andy Rachleff, Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen, Vinod Khosla, Paul Graham, Sam Altman, Naval, Elad Gil, Geoff Lewis, and Keith Rabois).

This piece aims to be as practical as possible. I included examples in every section, with a total of 54 company examples. I’ll also touch on my personal experience co-founding RemNote.com (backed by General Catalyst).

Content:

Problems

Problem-solving is how humanity makes progress. In theory, any problem can be solved except if its solution is prohibited by the laws of physics.

A solution to your own problem or one you notice is called an organic startup idea2. (See the questions that help you find organic startup in the last section of this post). These startups can be easy to build because you save time understanding your customers and what they want. YC claims that 70%3 of the ideas of the successful startups they surveyed were organic. One reason that these are more successful is that they are likely based on a real problem. Michael Seibel (managing director at YC) said4:

I would start thinking about problems. [A] lot of people keep little idea books with start-up ideas. I think they'd have a lot more success if they kept little problem books and wrote down notes on the problems that they encounter.

The most important aspect of a problem is its severity: How much time or money is the problem causing your customer or end user, and how frequently and urgently do they experience the problem? How much do they want a solution?

A solution in search of a problem (SISP) is often addressing a made-up and less severe problem. Though, as we’ll see in the next section, Andy Rachleff has a more optimistic view of SISPs.

In the last section of this post, I’ll also talk about the process of finding and discovering interesting problems.

Secrets and Trends

In economics, disbelief in secrets leads to faith in efficient markets. But the existence of financial bubbles shows that markets can have extraordinary inefficiencies—Peter Thiel (Zero to One)

In other words, a secret is a market inefficiency.

Similarly, Chamath Palihapitiya said5:

There is always a scarce resource somewhere. So whether it was all of us deciding to organize around safety, inventing language, creating money, building a machine, creating a smartphone, somewhere along the way, someone was asking the question, what is the next great problem that needs to be solved? Where I stand today, what is the scarce resource that exists? What limits progress?

Contrary to popular belief, the number of startup ideas and secrets is not shrinking. It is growing6. Humanity gains new desires and market inefficiencies with every new human on earth. Humanity’s future is infinite, as is the number of world-changing companies.

Similar to secrets, broader trends are often overlooked, though less secret. Trends are also referred to as the "why now" in pitch decks7. To identify secrets and trends, ask:

How is the world changing in fundamental ways?8

What valuable company is nobody building?9

What company would I like to own in 10 years?10

A way to assess the current market size is to ask11: 1. how many potential customers are there, and 2. how much will each of them be worth to you if everything goes right? This is summarized by the formula:

Market Size = (# of Customers) × (Revenue/Customer)

Predicting the future market size or latent demand is tricky. Many underestimated the potential market sizes of Airbnb, Lyft, and Uber because they didn’t understand the potential or future market size, demand elasticity12, and disruption potential of taxi and travel accommodations.

Andy Rachleff (co-founder of Benchmark) describes the importance of a deep understanding of what products a technology enables and how a product can address a desperate market as the quality of the insights13:

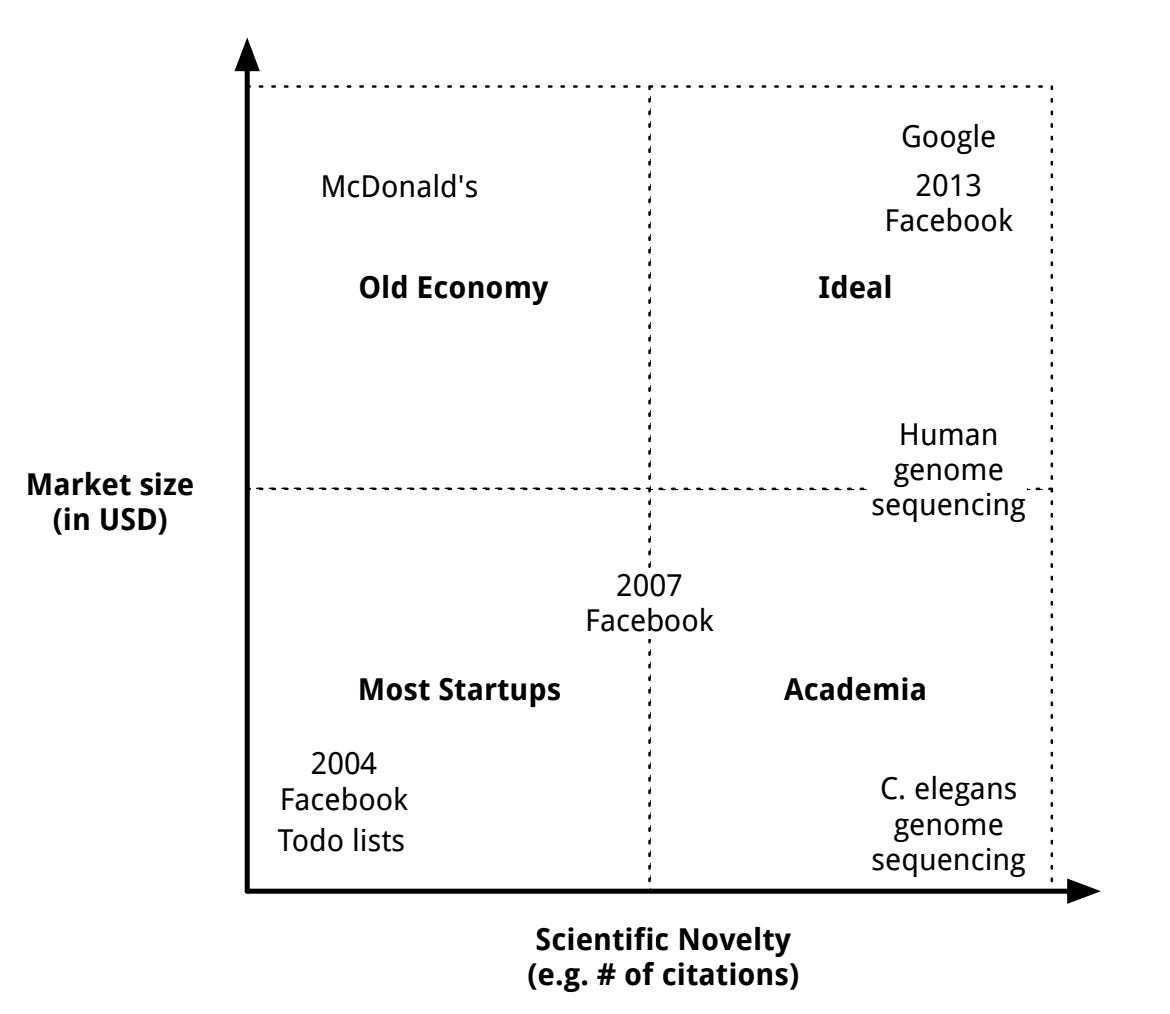

Almost everything you read about entrepreneurship would lead you to believe that entrepreneurs evaluate markets, look for problems, and come up with Solutions. That will lead you to the right and consensus quadrant14. That's really easy to do. Anybody can do that. What great technology entrepreneurs do is look for an inflection point in technology that enables a new product, and then they try to find a market that wants that product…

It’s all about the quality of the insight and if you’re able to find a market that is desperate for that insight. [Great founders] live in the future. They can see the implications of that inflection point, and what that can solve, way before anyone else can.

This framing closely mirrors the definition of an invention that Brian Arthur gave in his book The Nature Of Technology: What It Is And How It Evolves15. In his book, he explains that we invent by linking the following two aspects (conceptually & physically):

A demand,

An exploitable effect (or set of effects), i.e., principle

Examples:

Jeff Hawkins built PalmPilot’s PDAs for a price point of $300 by removing unnecessary functionality while everyone else was trying to build them for $2000. Hawkins understood the technology inflection points that cheap PDAs with a high margin were possible and saw the desperate demand for them.

Anne Wojcicki's 23andMe anticipated the continuously declining costs of genetic data, the rise of Web 2.0, and social networks. She transformed users into active research participants, pioneering a novel crowdsourced genetic study model, thereby disrupting incumbent research institutions like Stanford and Pfizer16.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) became viable once rare-earth barium copper oxide (REBCO) superconducting tapes were commercially available. These enabled the high-field, high-temperature magnets essential for CFS's compact tokamak designs, allowing for smaller, more cost-effective fusion reactors capable of net energy production.

Andy Rachleff explained that the idea of Wealthfront came when he learned about new APIs in the brokerage world that would enable building an automated investment service, replicating the sophisticated models of endowment funds, thereby making the models available to the masses17.

Founded in 2008, Twilio's founder, Jeff Lawson, realized that creating an easy-to-use and cost-effective communication API service had just become feasible, and he accurately anticipated the latent/growing demand for such services.

Peter Thiel differentiates secrets in nature and secrets in behavior. Similarly, we can differentiate between Technology trends and market trends:

Secret and Trend Types

Like surfers who aspire to greatness, the founders sought out their wave, often seeing it much sooner than almost anyone else. They had the foresight to see the future first, the insight to build the right kind of surfboard, the courage to paddle very far out into the ocean amongst the sharks (and naysayers) long before the wave hit, and ultimately the steely determination to ride atop the wave, even as it rose to scary heights, and broke in ways they couldn’t foresee.

—Greg McAdoo (ex. partner at Sequoia)18

Secrets in Nature

These are technological possibilities that are widely underappreciated. To find technology trends, we can ask:

Which technology or platform adoption curves are starting to hit scale over the next few years?

What’s the science fiction version of product X?

What did just recently become possible? (Any time you can think of something that is possible this year and wasn’t possible last year, you should pay attention).

What did just recently become necessary? (A good example here is Checkr, which does background checks for delivery startup gig workers).

What costs have plummeted or will plummet? (Many successful companies, including YouTube and Dropbox, were enabled by the plummeting database hosting costs).

A useful framework to evaluate the technologies behind a startup idea is that of disruptive/strong and sustaining/weak technologies. Keith Rabois (partner at Founders Fund) says that the most valuable companies are often built on the former, those that challenge the status quo and shift the paradigm19. Whilst strong technologies may initially seem expensive, risky, unusual, or toy-like20, they capture the imagination of enthusiasts. They tend to define new eras, forcing the world to evolve and mold to their requirements. In his post, Chris Dixon (partner at a16z) gives a few examples of pairs of strong and weak technologies:

Unlike disruptive technologies, incumbents are often quick to adopt sustaining or weak technologies. Generative AI might fall more into the weak technologies bucket because companies of all sizes are rapidly adopting it. However, the adoption itself represents a behavioral trend (see below).

Disruptive/strong technologies often develop according to the Perez21/Gartner/Amara22 hype cycle. That is, after an innovation trigger and peak of inflated expectations, there is a trough of disillusionment in which the technology loses in hype. During that time, a weak technology might appear nearer to mainstream adoption.

Similarly, the Founders Fund23 recommends commercializing the technologies that have languished:

[C]omputers and communication technologies advanced enormously (even if Windows 2000 is a far cry from Hal 9000) and the Internet has evolved into something far more powerful and pervasive than its architects had ever hoped for. But a lot of what seemed futuristic then remains futuristic now, in part because these technologies never received the sustained funding lavished on the electronics industries. Commercializing the technologies that have languished seems as good a place as any to start looking for ideas.

Examples:

In 1995, Nintendo released a virtual reality console called the “Virtual Boy” that sold dismally. In 2012, Oculus started working on its first headset, Oculus Rift.

In 2012, Databricks was founded by a team from U.C. Berkeley who noticed Silicon Valley tech companies successfully used a different technology, now known as Apache Spark, for AI and machine learning. Despite initial resistance due to its perceived academic nature, the team started Databricks to promote this technology, proving its enterprise readiness and potential to revolutionize the industry24.

In 2017, Vectordash (YC W19) tried to build a GPU cloud service focused on Machine Learning. The company pivoted into cloud gaming because of a lack of demand and eventually shut down. In 2022, many crypto-focused GPU server centers were underutilized, while LLM technology saw fast adoption. This enabled the success of Machine Learning focused GPU marketplaces like RunPod.io.

Secrets in Behavior

These are things that people don’t know about themselves or things they hide because they don’t want others to know. “Market trends” is a combined term for consumer or business behavior changes, regulation changes, etc. Marc Andreessen wrote25:

In a great market – a market with lots of real potential customers – the market pulls product out of the startup. The market needs to be fulfilled, and the market will be fulfilled, by the first viable product that comes along. The product doesn’t need to be great; it just has to basically work. And, the market doesn’t care how good the team is, as long as the team can produce that viable product.

To find secrets in behavior, you might ask:

What hacky, bizarre behavior could become mainstream26?

What is a trend (a long-term shift in behaviors or preferences often characterized by rapid growth), and what is a fad?27

Which behavior or usage sounds dumb but has traction? (A new mainstream behavior is often viewed as dumb in the beginning. Andrew Chen (at a16z) described this as the dumb idea paradox28.

What market is relatively small today, where something is changing to make it a big market tomorrow?29

What area has a growing customer base but they’re being dramatically underserved30 or overserved (enables low-end disruption)?31

Examples:

Mariam Naficy leveraged crowdsourcing and an untapped talent pool of bloggers to create Minted, a successful online design marketplace for high-end paper products, despite initial skepticism around the viability of print media32.

Robinhood capitalized on the interest of short-term, commission-free stock trading on mobile phones. Before Robinhood, wealthy individuals traded stocks mostly through financial institutions.

Affirm capitalized on the trend of millennials avoiding credit card debt by offering point-of-sale loans for e-commerce purchases.

Another strategy is to ask: which products, platforms, or behaviors are being bundled or unbundled?33

One approach is to take adjacent categories and determine which 20% of features have an 80% influence. Look at overlapping categories, and then start documenting the important features.

Examples:

Rippling created a suite of bundled but independently useful and compatible HR-related SaaS products. This creates a large surface for upselling their other products.34

Intercom bundled support chat, outbound messaging, onboarding, and analytics.

Pendo came about from consolidating analytics and in-app personalization.

RemNote (my first startup) capitalized on adoption of spaced repetition and knowledge management software. We noticed that many people were copying text from their note-taking apps into flashcard apps and solved this problem by creating a unified workspace for learning and thinking.

Narrative Violations & Mirages

Another type of Secrets is uncovered by violating narrative mirages, i.e., misleading or incorrect ideas about the world. They are fueled by popular narratives that create an illusion of a market or technology, leading to a rush of investments and potential bubbles.

This phenomenon, termed Narrative Mirages by Geoff Lewis (founder/VC at Bedrock Capital)35, can often mislead investors and entrepreneurs into believing in the promise of a nascent startup or a new market category.

A narrative violation occurs if an idea, investment thesis, or knowledge about a company, market, or technology contradicts the popular narrative. These often represent great opportunities. In his letter, Lewis goes on to list some examples:

Howard Marks, founder of Oaktree Capital wrote36:

Most great investments begin in discomfort. The things most people feel good about – investments where the underlying premise is widely accepted, the recent performance has been positive, and the outlook is rosy – are unlikely to be available at bargain prices. Rather, bargains are usually found among things that are controversial, that people are pessimistic about, and that have been performing badly of late.

[…]

Unconventional behavior is the only road to superior investment results, but it isn’t for everyone. In addition to superior skill, successful investing requires the ability to look wrong for a while and survive some mistakes.

Narrowing down the search space (Where to Look)

In my own exploration, I found focusing on a narrow problem space extremely useful. This focus could mean focusing on a particular industry, customer, technology, or regulatory space. This focus is helpful because 1. your learnings from customer discovery calls within an industry will compound, and 2. it helps you to ensure the ideas you focus on have a good founder market fit.

Founder Market Fit

To increase your founder market fit, searching for an idea in fields that leverage your unique background, skills, and resources can be productive.

It might make you aware of changes or problems others can’t see. To find organic startup ideas for each life experience, internship, job, etc., think carefully about the following:

What problems did you come across?

What did you learn that other people don’t know?

What problems have you been in a special position to see?

For B2B ideas, you can ask:

What internal products have you built again and again at past companies?

What’s a tool you wish you had (and would have paid a lot of money for) at your previous companies?

Schlep blindness spaces

A place to look for secrets is where no one else is looking. Frequently overlooked ideas are those occluded by schlep blindness, as Paul Graham describes. For example, founders tend to shrink from uncomfortable idea spaces such as payments or payroll software, as they require complex state licenses. Boring ideas get left on the table.

Prone industries and markets are another good place to look for ideas. As Paul Graham wrote37:

Since startups often garbage-collect broken or stagnant companies and industries, it can be a good trick to look for those that are dying or deserve to, and try to imagine what kind of company would profit from their demise. For example, journalism is in free fall at the moment. But there may still be money to be made from something like journalism. What sort of company might cause people in the future to say "this replaced journalism" on some axis?

Many companies in these spaces are slowed down by bureaucracy and navel-gazing38.

Marketplace Criteria

Criteria for marketplace ideas are39:

Currently massive or growing into a massive market size

Manual existing processes

Inefficient capacity utilization

Flexport rationalized international logistics to make optimal use of cargo space.

SpaceX’s reusable rockets reduce the cost per launch.

Opendoor’s home sales process reduces unoccupied homes.

Airbnb took an underutilized resource, broke it up into smaller modular units (day-based sublets), and created a low-friction marketplace to sell those units.

High fragmentation (on the demand and supply side)

I.e., there are many small market participants, leading to inefficiencies due to a lack of standardization and complexity of the purchase process.

Low NPS (net promoter score)

It is also helpful to think of any marketplace idea as a solution that reduces certain transaction costs (Dan Hockenmaier has a great post about this40). I also wrote about transaction cost and risk elimitation on this blog.

Proxies and Competition

A proxy is a large and successful company that does something similar to your potential startup idea but is not a competitor. However, Thiel pointed out that ideas based on an analogy to a different business are more likely to lack a true secret because others can also come up with the analogy. Similarly, bringing an existing idea to a different platform or applying it in a different industry can be fruitful.

Examples:

Rappi, the most successful food delivery startup in Latin America, used the success of DoorDash as a proxy41.

Before Airbnb, there was Vrbo (founded in 1995) and couch surfing42. Neither facilitated payments nor provided professional photographers to their landlord customers.

The founders of Zip got advice from their YC Partner to look for a large market with entrenched companies that weren’t great, which led them to the procurement space (Incumbents here include Coupa and Bill.com)43.

Instagram brought the existing idea of photo sharing from popular desktop/web-based platforms like Flickr to mobile.

Right after Amazon showcased its first smart, checkout-free retail store, Standard Cognition (or Standard AI) realized that every grocery store would want the same technology.

Palantir took big data analytics concepts (primarily used in consumer-facing industries for targeted advertising and recommendations) and applied them in the defense, security, and government sectors.

Counterintuitively, competition can be a sign of a good startup idea44. However, your startup idea typically needs to leverage a new insight (that makes your solution 10x better) to dominate your competition. Paul Graham wrote45:

Worrying that you're late is one of the signs of a good idea. [...] You don't need to worry about entering a "crowded market" so long as you have a thesis about what everyone else in it is overlooking. In fact, that's a very promising starting point. Google was that type of idea. Your thesis has to be more precise…

Examples:

Despite many other file-hosting competitors, Dropbox succeeded due to a significantly better UX, allowing users to connect the app to their operating system and sync files automatically.

Google’s secret was its superior page rank algorithm.

Facebook had fewer bugs and churn than Friendster and felt safer46.

Exploration

Many of the best secrets are earned secrets. They are discovered while exploring a problem space.

Curiosity was designed by evolution to uncover problems and gaps in understanding, which is why it is a powerful drive to find areas for startup ideas. Vanta’s founder, Christina Cacioppo, said47:

There was this curiosity of thinking, these are smart, motivated people. How did they mess [their security/complience] up? That puzzle was just interesting to me, and it informed what Vanta ended up becoming.

Do you have some ideas already? Chris Dixon recommends creating a spreadsheet with your ideas and talking through each of them with the smartest people you know48.

Nat Turner (who sold Flatiron Health for $1.9 billion) has an excellent approach to finding startup ideas, which might be described as “pitch to get feedback and iterate”. He recommends49:

Begin with a general space of interest and look for any seed of an idea

Ask: What are the interesting problems in this space, and what is the root cause of these problems?

Network like crazy in the industry and take introductions extremely seriously

Create a deck and start pitching to anyone smart and relevant you can find on the specific idea. Take meticulous notes and follow up.

Tweak the deck between every meeting, hack together a demo, and start pitching (pre-sell software that doesn’t exist yet but will)

Find a trusted group of advisors to discuss key learnings from the field and get feedback.

Continue to iterate as hard and fast as possible on the feedback you’ve received.

Example: While still in college, Turner was interning at VideoEgg. After an executive during a sales meeting said, “We want to advertise on VideoEgg, but we don’t have a big production company to build a video ad”, he and his friend Zack Weinberg sat down and began to think of solutions. But instead of just researching the idea or talking casually with others in the online advertising space, they immediately began to pitch. Turner recounts the early days of Invite Media:

We pitched everyone. We pitched potential advisors, investors, potential customers, friends, everyone. I can remember hundreds of meetings we had.

This research process aims to attain a sophisticated understanding of the problem space. A good startup idea is based on 100+ interviews rather than just 10.

From talking to several succesfull founders this process usually takes between 2 and 12 months.

Another approach is what I’d call the Ideal Customer Profile (ICP) or Title focused approach. Brian Long who co-founded the SMS marketing company Attentive outlined this interview template in his book "Problem Hunting”50:

What is your official title, and how long have you been in this role? How did you get this role?

What are your primary responsibilities?

We aim to build products that solve problems for you and your peers. What are the top three problems in your job today?

For each of the top three problems (repeat this section for problems #1, #2, and #3):

Can you explain more about this problem?

Why is it a problem?

What metrics track this issue?

What have you done to try and fix it?

On a scale from 1 to 10, how significant is this problem today?

9-10 == burning problem

Why do you feel that way?

What are the top three problems for your company today?

repeat 4.

Is there anything you'd like to emphasize or that we might have missed?

If you were starting a company in this industry today, what would you focus on?

Do you have any other questions or feedback?

Would you be open to a follow-up conversation? What's the best way to reach you?

As mentioned in the introduction, the success of a startup idea is inherently unpredictable, which is why assuming predictable growth in a trend is error-prone. Existing secrets might become irrelevant, and trends might die down, but new ones can emerge.

Exploring the idea maze before and during the company building process is an open-ended process. Paths from an initial niche idea into a giant company are hard to see. Good startup ideas can morph into great ones.

Examples:

Airbnb’s Brian Chesky, for example, read about major inefficiencies in the hotel industry after trying to rent out his air mattress.

Zillow’s Rich Barton found the problem that price discovery is broken. When trying his original idea of running an auction on every house, he discovered the Zestimate (a house price estimation service).

Ramp: After Eric Glyman’s startup Paribus was acquired by Capital One, he talked to many customers in their credit card division. He asked, “Do you want points, cash back, or something different for rewards?” He found that they didn’t want any of that and just wanted to be better off. This led to the idea of a B2B credit card that helps you save money51. This is also an example of identifying a behavioral trend/secret.

Coinbase’s founder Brian Armstrong applied to YC with a p2p bitcoin transfer application. He pivoted to focus on the problem of buying bitcoin52.

Pinwheel's co-founders initially focused on health savings accounts (HSA), but found themselves struggling integrating with various payroll systems. Talking to people about their income and employment data problems, they noticed particular excitement about them offering direct-deposit switching (the process of changing the users linked bank account), which became their wedge into the market48.

PillPack’s co-founders identified an innovative medication packaging solution and saw multiple potential routes for market entry (or “paths to value”), either complementing or challenging traditional pharmacies like CVS and Walgreens53.

Twitch’s original idea was to create an online reality TV show.

Lattice’s co-founder, Jack Altman, first built a tool for OKR tracking. It turned out that software wasn’t a good solution for managing OKRs. However, by building relationships with and talking to potential customers, they learned about their problems by conducting 360 performance reviews54.

Scale AI’s original idea was to make it easier to book doctor's appointments. After discovering that interfacing with hospitals’ outdated information systems would be difficult, they revised their idea to put people on the back end to interface with hospitals. Users would input their insurance information, availability, location, etc., on Scale’s website, and they would take this information and call the hospitals and book an appointment for them. Next, they discovered that hiring the contractors for this work was not easy, leading to the idea of an API for human labor. Finally, they realized that the machine learning data labeling use case was in strong demand and decided to focus on that completely55.

PayPal went through five business models before it found something that worked (including security software for Palm Pilots, sending money between Palm Pilots, and later sending money between emails)56.

Often, an innovation is combining two existing ideas. If you develop a better idea that fits into your original one, you can try to merge them.

Example: when coming up with the idea of Scribd, Trip Adler combined the idea of 1. “A way for academics, creative writers, or anyone to publish online more easily”, and 2. “The YouTube for all kinds of writing”57.

This process is about deeply understanding the idea space and articulating the insight. Andy Rachleff explains58:

People who are really good at what they do, who have a tremendous command of what they do, are able to explain it in very, very simple terms, and they are the ones who are more likely to be able to pull off the non-consensus bet.

[…]

When you succeed you often stumble upon the market that's desperate.

Thanks to Robert Wachen, Charlie Curnin, Andrew Duca, Vincent Weisser, Miles McCain, Sven Schnieders, Jason Zhao, and Bani Singh for feedback on drafts of this.

Jared Friedman quotes the number in the video at ~20:22. Blog version here: ycombinator.com/library/8g-how-to-get-startup-ideas

How to Get and Test Startup Ideas - Michael Seibel

Paul Graham recently wrote, “Knowledge expands fractally, and from a distance its edges look smooth, but once you learn enough to get close to one, they turn out to be full of gaps.”: paulgraham.com/greatwork.html

Or, more exactly: “Why could it not have been done two years ago, and why will two years in the future be too late?” as Sam Altman explains in the CS183 class at Stanford.

Zero to One, Peter Thiel, Chapter 8: Secrets

My old college professor and mentor, Roland Fassauer, once said this to me (applying an Amazon-style thinking backwards reframing).

Demand elasticity is influenced by dropping costs, as explained by the Jevons Paradox. It holds that if the marginal cost of a good with elastic demand (e.g., compute or distribution) goes down, the demand more than increases to compensate.

The art of starting a startup — Gagan Biyani’s advice…: review.firstround.com/podcast/episode-56, podcast version

As explained by Peter Thiel and Ken Howery at Founders Fund, on page 59 of The Innovator's Solution

Marc Andreessen and Jim Barksdale on the HBR IdeaCast.

This is also an example of the exploitation of a market inefficiency as DoorDash couldn’t effectively serve all the demand in other geographies. More in this post: spiff.com/startup-ideas-how-the-best-founders-get-them-and-why-novelty-is-overrated/#market-inefficiencies

startups die of suicide, not murder

paulgraham.com/startupideas.html > “Competition”

Loonshots: How to Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries (Amazon)

Amazing article